Southwest Airlines has been running an ad during the NCAA basketball tournament that touts its frugal ways. The ad is transparent, honest and pragmatic.

“You save money dealing directly with us,” the voiceover says of its website, and “we save money dealing directly with you.”

From there, the ad touts its low airfares—see? See?—as a clean extension of the value proposition behind the company.

I love this commercial for its win-win approach. Southwest is calling out on national television that they’re not playing games. If you work with us, they say, it costs us less, and in turn, we’ll help you spend less, too. In today’s savvy shopping environment, it’s great to see a brand talk frankly about minding costs and passing savings onto customers.

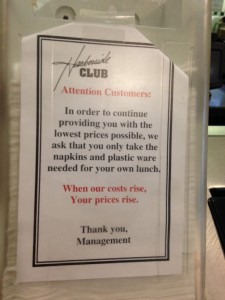

Compare this with the sign I see in the building cafeteria when I’m in my New Jersey office. It covers the front of every napkin dispenser they have.

“When our costs rise,” it says, in bold red type, “Your [sic] prices rise.”

This little sign could be a win-win, like Southwest’s ad. But it’s not. It’s antagonistic. It’s a threat. There’s no mutual benefit, no collaboration, just a warning. Waste our money, and we’ll take it right out of your pocket, bucko.

It helps that the cafeteria is the only place to grab lunch without a decent walk. They have a bit of a monopoly, and it shows: the food is somewhat expensive, the cooks refuse to go off-script, and certain stations randomly don’t open some days. All of which mirrors the attitude on the napkin dispensers. Don’t mess with me, eater. I’m all you’ve got.

The cafeteria misses an opportunity to create customer loyalty that could have been communicated simply and effectively. How much better would the napkin dispenser make customers feel if it said, “Keeping costs down keeps your lunch prices down,” instead of going toe-to-toe with diners?